Exhibit of the month

I bind down, bury deeply and make disappear from humanity…

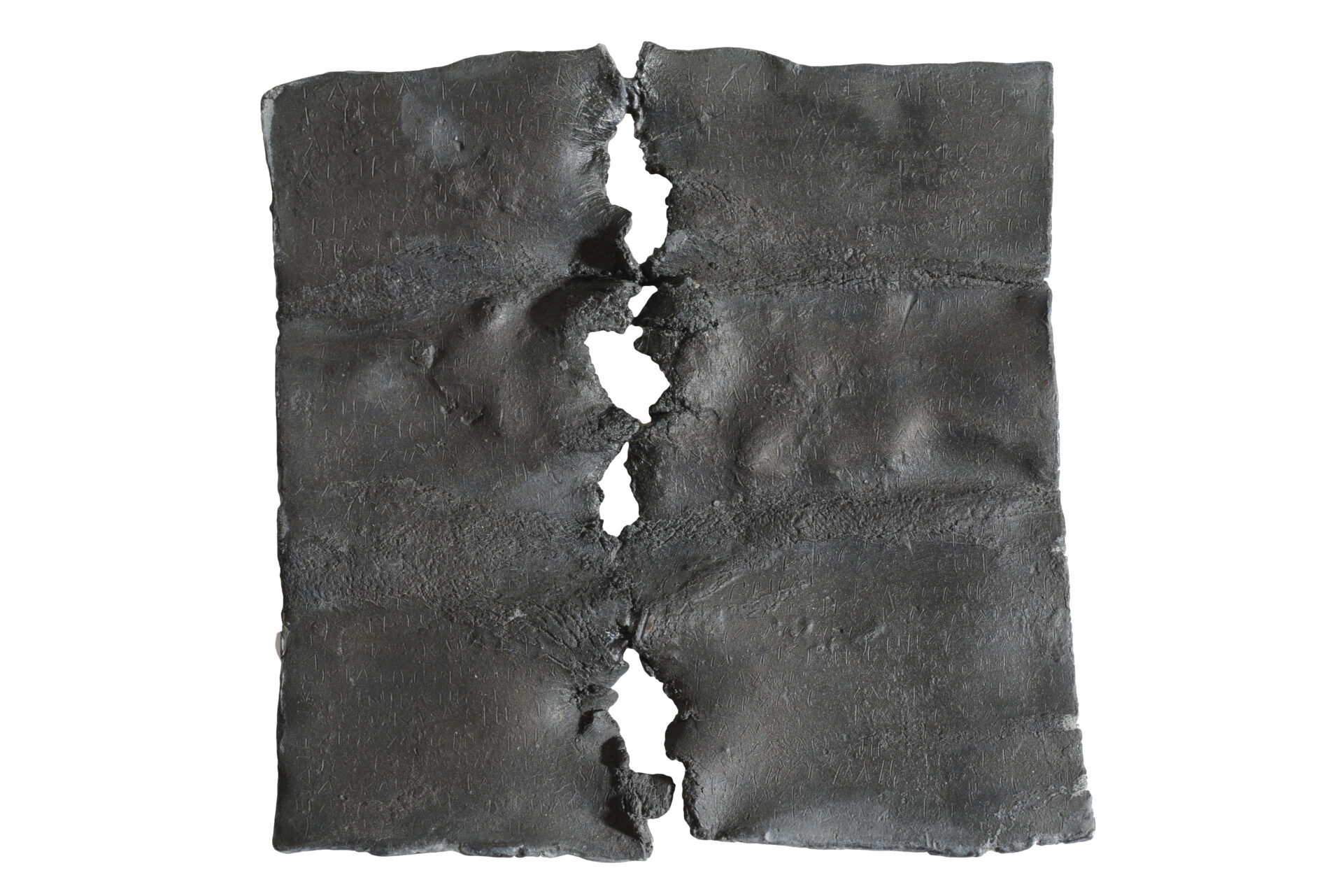

Lead binding tablet

Metalwork Collection, inv. no. X 14470

Provenance: Athens

Dimensions: width 7.5 cm, height 8.3 cm, thickness 1.5 cm

Date: 345-335 BC

Display location: Room 38, Showcase 55 (no. 13)

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Museum acquired a unique lead binding tablet[1] with an extensive curse engraved in Attic dialect on both sides, outcome of a purchase. It was reported to have been found in Athens, in the area of Agios Savvas, which is identified with the small church on Iera Odos, in the region Eleonas. This is probably the location of an ancient sanctuary dedicated to Zeus Meilichios mentioned by the traveler Pausanias (I, 37,4).

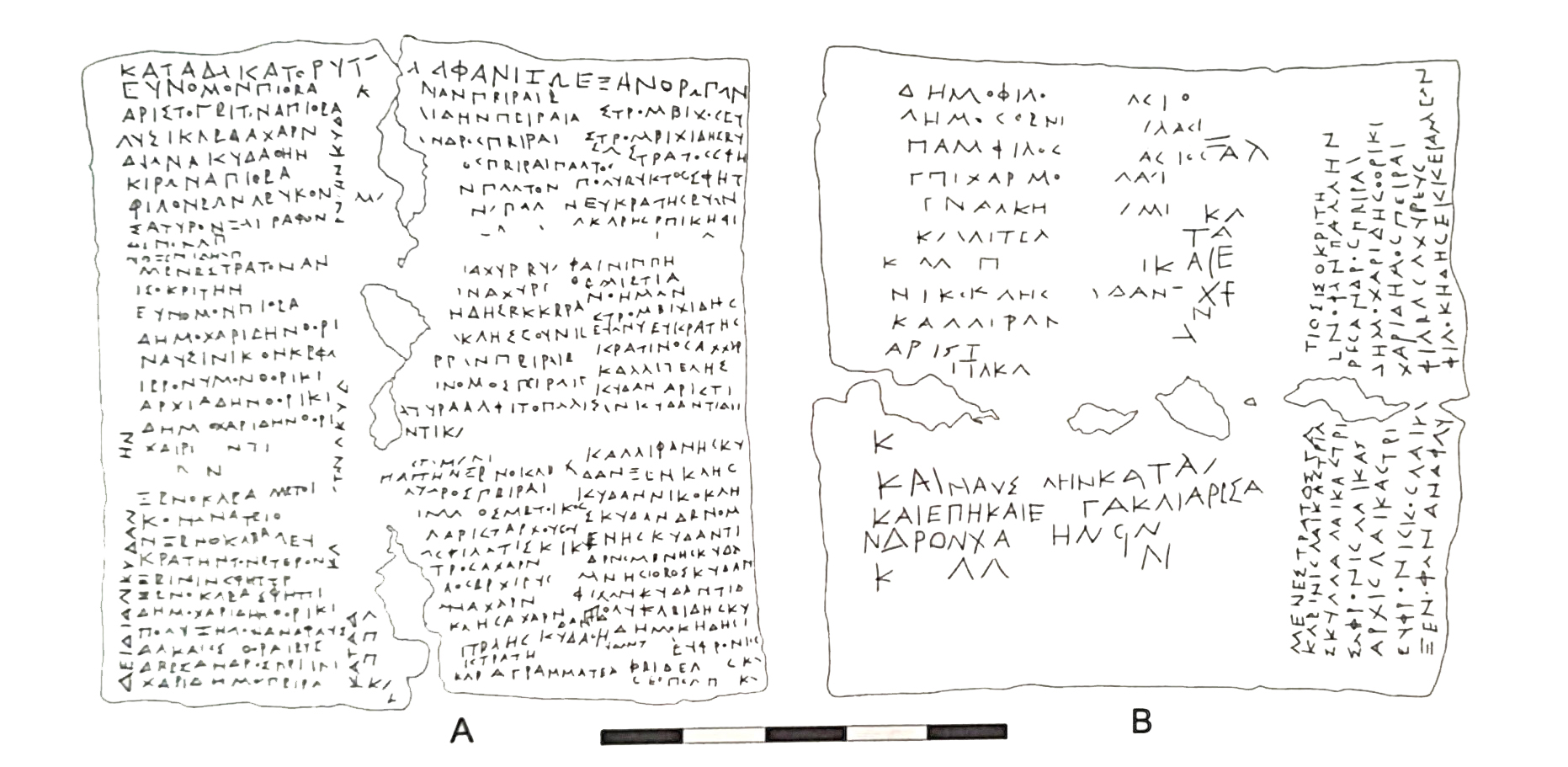

The square plate was originally wrapped twice and pierced with a now lost nail. The piercing is responsible for the loss of a small part of the inscription, which nevertheless remains an impressive list of 111 names, mostly of Athenian citizens. The anonymous offender introduces the curse with the phrase “I bind, bury deeply, make disappear from humanity”. On the reverse side the typical phrase “I bind both words and deeds” is inserted. The names, arranged in columns[2], are accompanied in most cases by the demotic (demos-name), an element of identity for the Athenian citizens. A few names are repeated. The victims number at least 96 persons, including 30 well-known Athenians of the 4th century BC, who were patrons, trierarchs, public officers, owners of land and slaves. In the list we find members of the anti-Macedonian faction of Lycurgus, Hyperides and Demosthenes (e.g. Polyeuctos and Xenocles from the demos of Sfettos), but also the orator Aristogeiton, sycophant of Hyperides and Demosthenes. There are also various professionals (painter, straw seller, grain seller), eight women, four of whom are prostitutes, a male prostitute as well, and finally two metics (foreign residents). The inscription is a treasure for the 4th c. BC portraiture of Athens and dated precisely 345-335 BC. The reason for existence of this curse remains a matter of conjecture. It may have been related to a party dispute or to the activity of slanderers in political trials or to a commercial issue (e.g. illegal export of wheat), or perhaps it targeted the members of a private society/club of upper class males.

In antiquity, the performance of acts related to magic is attested. Curse tablets, which are primarily objects of a magical nature, appeared in the late 6th century BC in Greek colonies in Sicily, then in Attica, from where they spread to mainland Greece and the islands. Until late antiquity they were found throughout the Mediterranean world[3]. Often wrapped and pierced with nails [4], they were secretly deposited in water “sources” (wells, baths, fountains, cisterns), in sacred places, rarely in houses, public buildings, roads. They were considered most effective in graves, preferably of people who died at a young age or violently or who were left unburied or buried without much care. The souls of these dead were on the borderline between the Underworld and the world of the living[5]. The offenders took advantage of the souls’ posthumous restlessness in order to control their anger and direct it against their own opponents. The latter were being “bound” and the curse was being transferred through the souls to the Underworld in order to find the target with the help of chthonic deities such as Hades, Persephone, Hecate, Lethe, Hermes, who were often invoked in the curses[6]. Curses concern affairs of judicial, erotic (love spells), agonistic or other character. The choice of lead as the defixiones constructive material is due to the fact that it is easily wrapped, engraved and read, but mainly that it was abundant and accessible as a by-product of silver mining. Interestingly, it is associated with magical properties because of its physical characteristics, such as its grey colour, cold feel to the touch and durability. In the context of magical binding practices, the bound effigies were also used, i.e. almost exclusively male figures, made of lead or wax, and more rarely of bronze or clay, with their hands tied behind their back, sometimes their feet as well. They were objects for the practice of sympathetic magic, based on the correspondence between the object depicted and the intended effect.

In ancient times the curse tablets evolved into a popular way of dealing with one’s enemies, while today into a valuable set of epigraphic, archaeological and partly religious value shedding simultaneously light on the thinking of the average people.

[1] The definition for defixiones, as expressed by D.R. Jordan, one of the most important scholars absorbed in the study of curse tablets, is the following:

Defixiones, more commonly known as curse tablets, are inscribed pieces of lead, usually in the form of small, thin sheets, intended to influence, by supernatural means, the actions or welfare of persons or animals against their will [βλ. D.R. Jordan, “A Survey of Greek Defixiones Not Included in the Special Corpora”, Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 26 (1985), 151].

[2] On side A there are 3 columns of names, while on side B we see a less careful arrangement of 4 columns, of which 2 are parallel to the side A columns and the other 2 are perpendicular to the first. The arrangement in columns, as in public documents, has been considered possibly as an example of the known magical practice concerning the use of authority symbols of the normal real-life world.

[3] The majority of the preserved curses are written in Greek, followed by Latin inscriptions dating from the 2nd c. BC onwards. There is a very limited number of Etruscan and Oscan, also Celtic and some probably written in Iberian languages.

[4] IG II/III³ 8, 1, 32 Inscriptiones Graecae

[5] Plato (Phaedo 81c–d) mentions the belief that shortly after death the souls, afraid of Ηades, were still active around the tombs, close to which people have seen some shadowy phenomena of souls and images/eidola. The representation of souls/eidola on Athenian white-ground lekythoi, a group of vases that was produced almost exclusively for funeral purposes, may attest that belief (see J. Stroszeck 2021, 24-25)

[6] The use of defixiones was probably accompanied by other rituals, such as the utterance of magic phrases, the performance of specific movements, or the choice of specific day and time of day for the secret deposition.

Alexandra Chatzipanagiotou

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Curbera, J., Inscriptiones Atticae Euclidis anno posteriores, ed. tertia. Pars VIII: Miscellanea. Fasc. 1: Defixiones Atticae, Berlin 2024, 96-99, no. 188, pl. 5 [= IG II/III³ 8, 1, 188 Inscriptiones Graecae]

Humphreys, S.C., 2010, “A Paranoiac Sycophant? The Curse Tablet NM 14470”, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigrafik 172 (2010), 85-86.

Jordan, D.R., “A Survey of Greek Defixiones Not Included in the Special Corpora”, Greek Roman and Byzantine Studies 26 (1985), 164, no. 48.

Jordan, D.R. – Curbera, J., “A Lead curse tablet in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens”, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigrafik 166 (2008), 135-150.

Chaniotis, A. – Kaltsas, Ν. – Mylonopoulos, Ι. (eds.), A world of Emotions. Ancient Greece, 700 BC-200 AD, Exhibition Catalogue, New York 2017, 182, no. 84 (Κ. Bairami).

SELECTED GENERAL BIBLIOGRAPHY

For binding practices and magic:

Αβαγιαννού, Α., Η Μαγεία στην Αρχαία Ελλάδα, Αθήνα 2008, 49–81. “Η Μαγεία στην Αρχαία Ελλάδα” – Συλλογικό έργο – Ανοικτή Βιβλιοθήκη

Eidinow, E., Oracles, Curses and Risk among the Ancient Greeks, Oxford 2007.

Faraone, C.A., “Binding and Burying the Forces of Evil: The Defensive Use of ‘Voodoo Dolls’ in Ancient Greece.” Classical Antiquity 10 (1991), 165–205.

Franek J. – Urbanova, D., “May Their Limbs Melt, Just as This Lead Shall Melt…”: Sympathetic Magic and Similia Similibus Formulae in Greek and Latin Curse Tablets (Part 1). Philologia Classica 2019, 14(1), 27–55. https://doi.org/10.21638/11701/spbu20.2019.103

Gager, J., Curse Tablets and Binding Spells from the Ancient World, Oxford 1992.

Ogden, D., “Binding Spells: Curse Tablets and Voodoo Dolls in the Greek and Roman Worlds,” in: V. Flint, R. Gordon, G. Luck, D. Ogden (Eds.), Witchcraft and Magic in Europe: Ancient Greece and Rome, London 1999, 1–90.

Stroszeck, J., “The archaeological contexts of curse tablets in the Athenian Kerameikos”, in Faraone, Ch.A. – Polinskaya, I. (eds), Curses in Context III: Greek Curse Tablets of the Classical and Hellenistic Periods, Papers and Monographs from the Norwegian Institute at Athens, volume 12, Athens 2021, 21-48.

For Agios Savvas, Eleonas region:

Παπαχατζή, Ν., Παυσανίου Ελλάδος Περιήγησις, Αττικά, Αθήνα 1974, 467-468.

Τσιριγώτη – Δρακωτού, Ι., «Η πορεία της Ιεράς οδού και η σημασία της», Αρχαιολογία 43 (1992), 29-30. https://www.archaiologia.gr/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/43-6.pdf