Memories 1940-1944

The rescue of the statues

It was a resurrection dance of rising figures…

that filled you with mad joy.

George Seferis

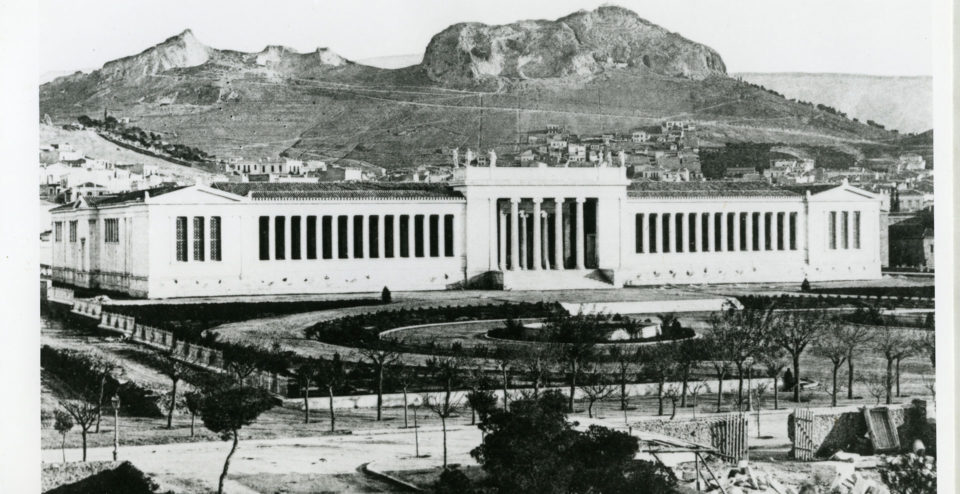

On the occasion of the national anniversary of the 28th October the National Archaeological Museum publishes valuable archive pictures from the chronicle of the concealment of antiquities, as these were put on display during the years 2016-19 in exhibitions of historical photography but also in other celebratory events.

In the shadow of war and throughout the occupation the employees of the first museum of the country were assigned the task of safeguarding the archaeological treasures against destruction and looting. «The archaeological service found itself in the irrational position of destroying the work that generations of Greek archaeologists had created». «I mean primarily the dissolution of the museums and the burial of antiquities in the soil, in crypts, in treasuries, in caves» Vasileios Petrakos reports, in the periodical Mentor of 1994 where a detailed account of the fate of antiquities during the period of 1940-1944 is given.

Testimonies and personal experiences of Semni Karouzou relating to that dramatic period were presented in March 1967 and published in 1984 in the Proceedings of the First Congress of the Greek Archaeologists Association. «When the occupation army entered the capital in April 1941, the task of concealing the ancient treasures of the National Museum had already been completed» the Ephor of Vases and Minor Arts mentions.

Indeed, on the 11th of November 1940 the Directorate of Archaeology of the Ministry of Education had issued general technical instructions for the protection of the museums from air raids. A titanic effort was then undertaken across the country by the committees for the concealment and safety of museum exhibits.

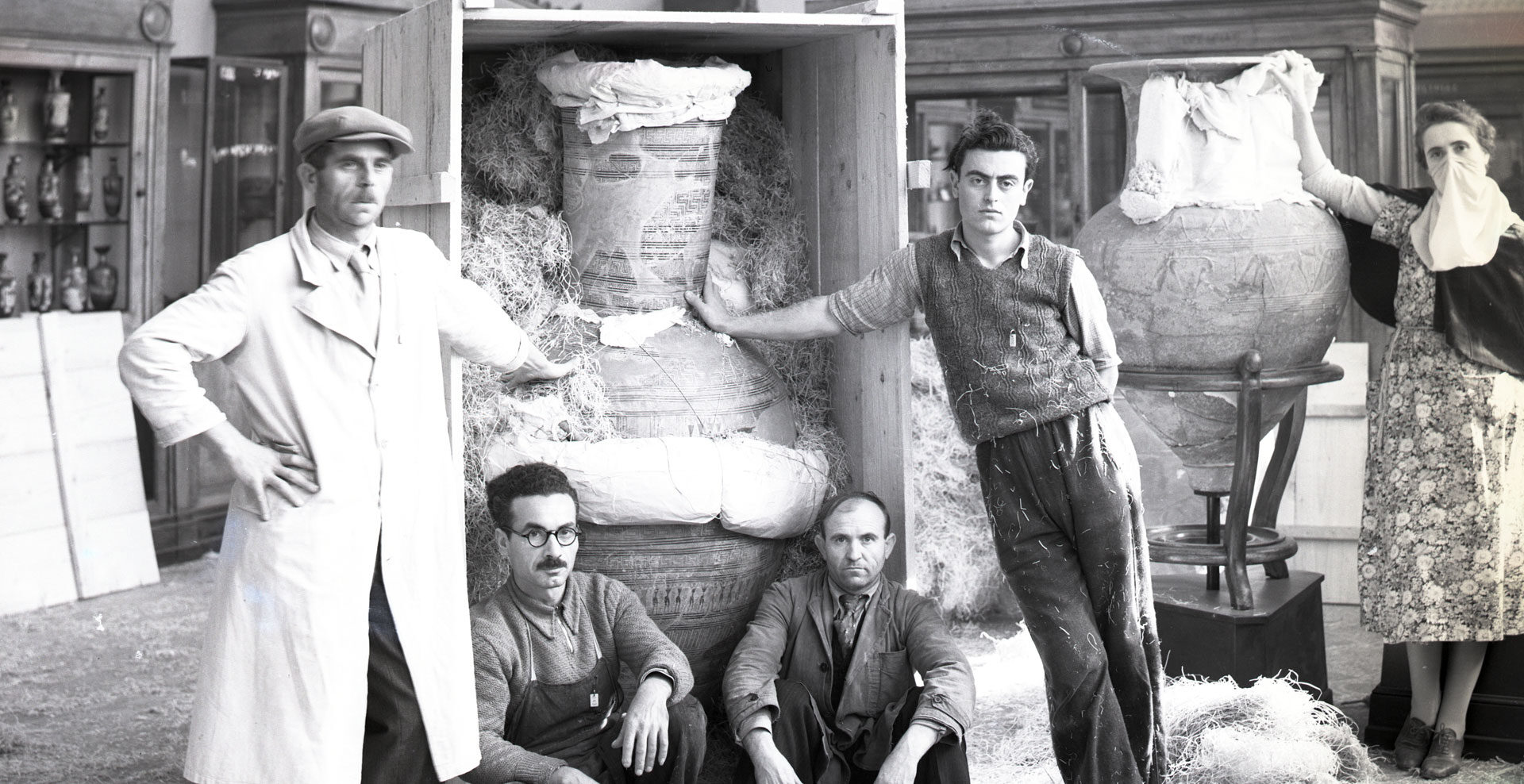

Referring specifically to the National Archaeological Museum Semni Karouzou hands down to us: «It took six whole months, over the entire duration of the epic advance on the Albanian front, for our antiquities to be safely stored, the fate of which was a matter of such great concern to the people upon hearing about the war… Very early in the morning before the moonset, those who had undertaken this task were gathering to work in the Museum, it was night when they were leaving to go home».

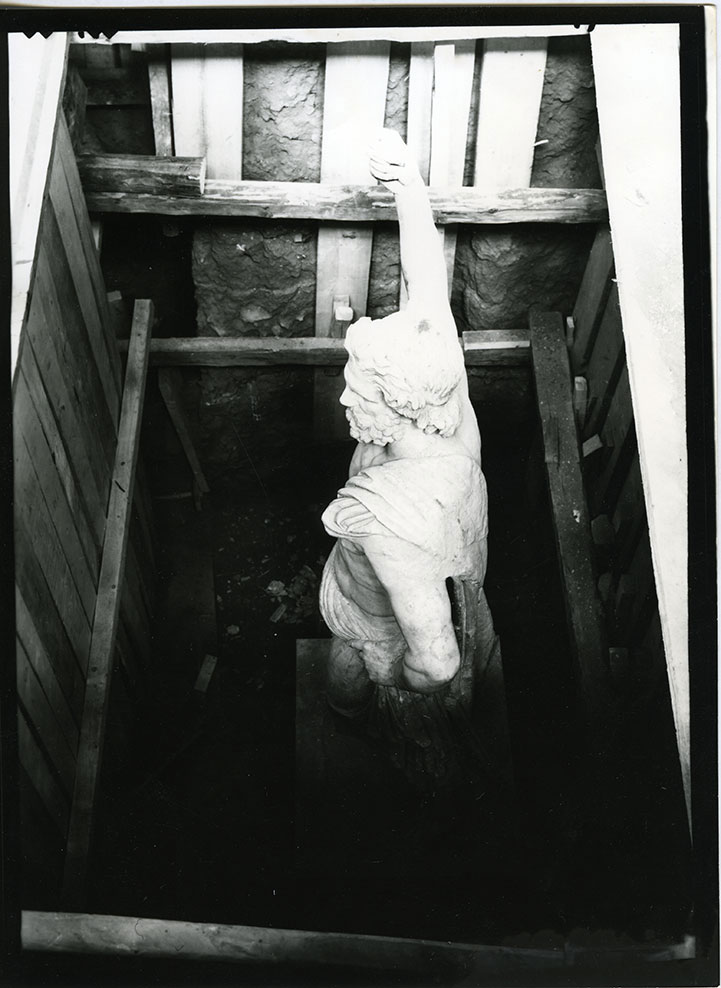

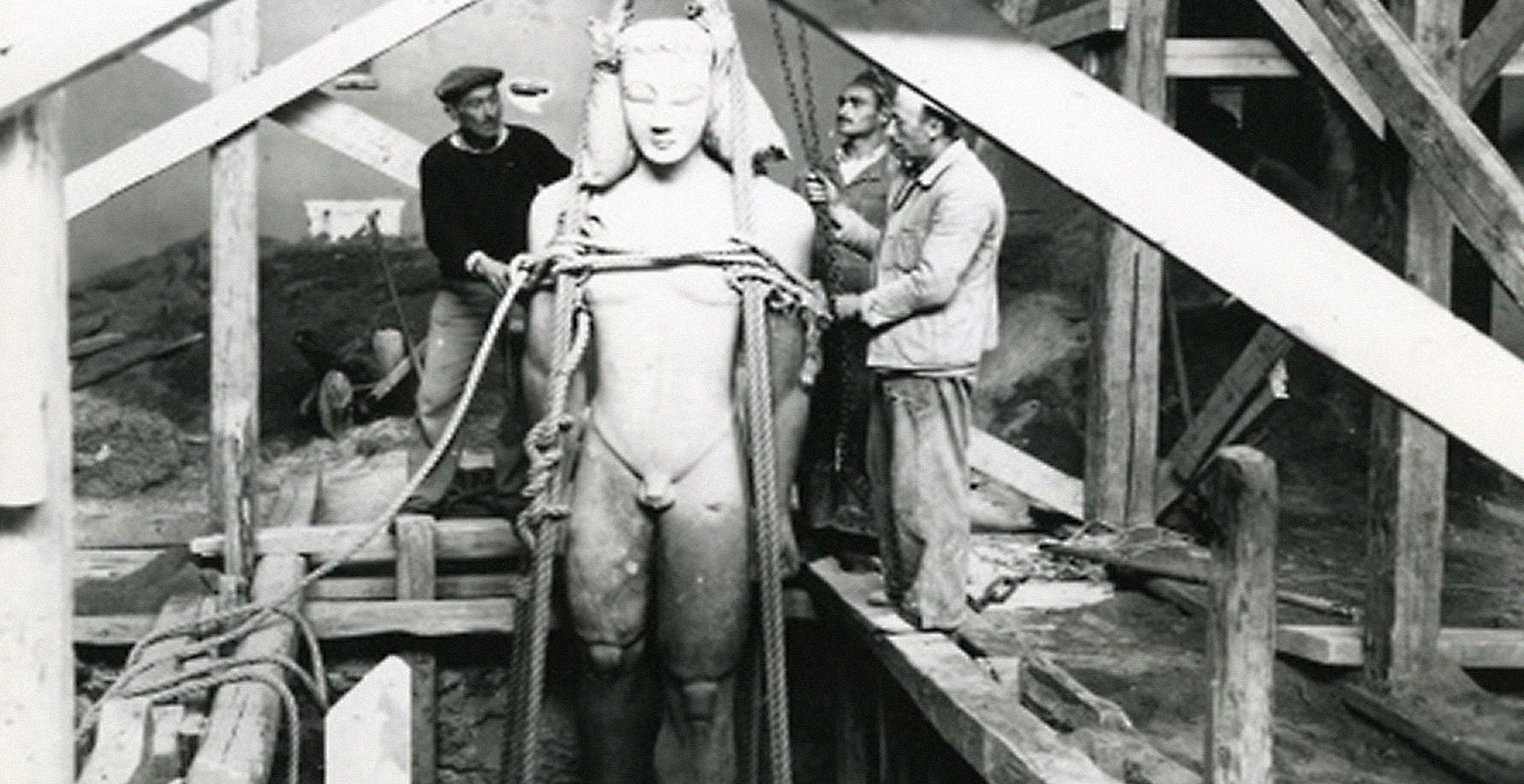

And while on the war front our heroic soldiers were accomplishing the epic feat of the «No» crying out the famous battle cry «Aera» («Air»), another catchphrase sounded in the spaces of the museum. «Fire up» was one of the commands given by the sculptor Andreas Panagiotakis when the craftsmen pulled with chains and ropes the marble statues in order to place them in large pits they had opened in the north wing.

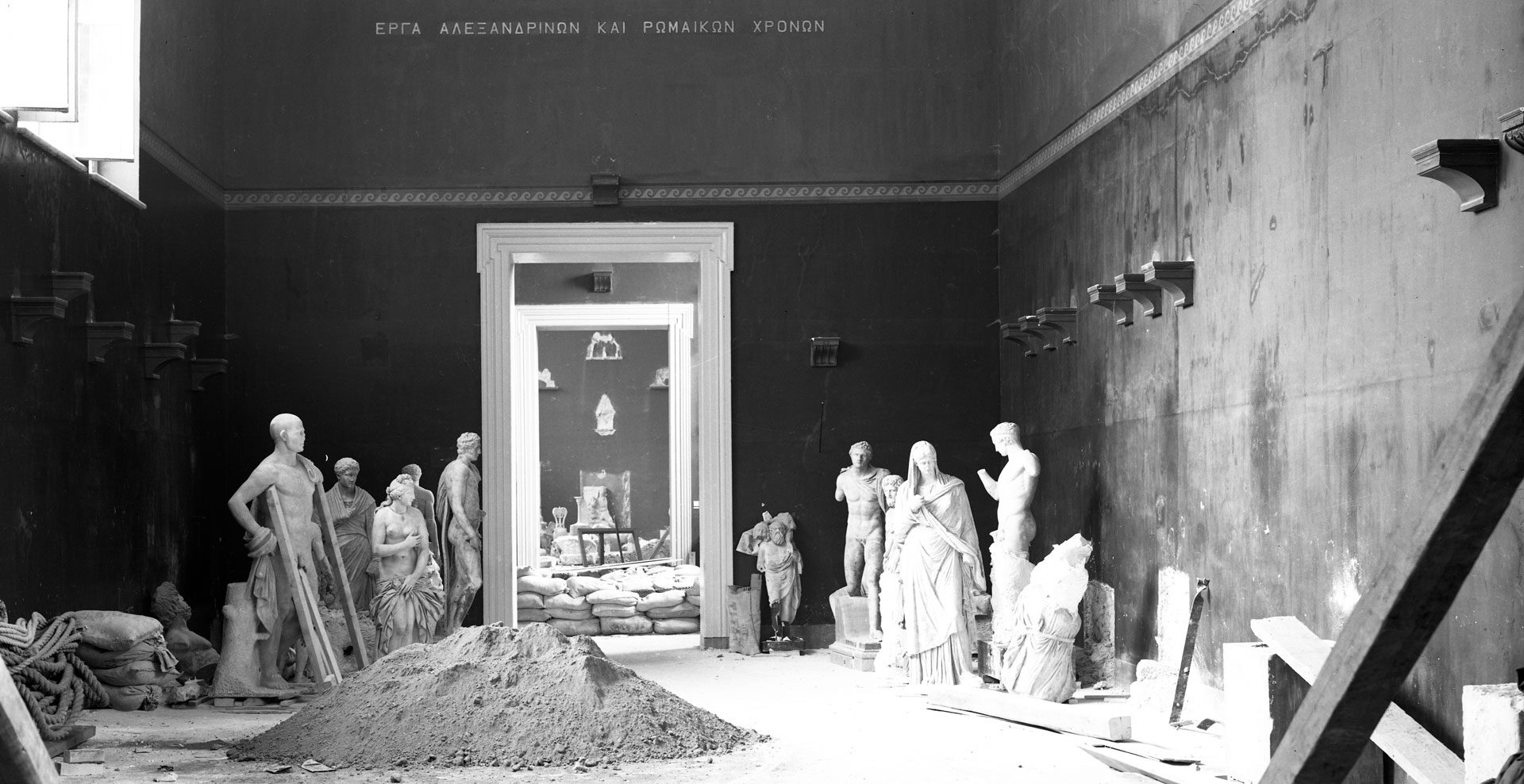

In April 1941 the museum looked deserted. Sculptures, bronze and clay artworks had been packed and transported to various raid shelters in Athens (35 crates were stored in the cave of the Enneakrounos and another 22 in the prison of Socrates) the gold objects had been hidden away in the basements of the Bank of Greece, the large statues had been deposited in large trenches that were dug in the floor of the museum halls.

On the following day of the invasion of the Nazi troops in Athens, Semni Karouzou and Christos Karouzos sent their resignation from their position as members of the German Archaeological Institute. «Since many years the Institute had stopped having any relation to Science and it was imperative to cut short their hope that they would achieve anything at all by making an attempt, which I could guess would be systematic and methodical, to stain the reputation of us all with innocent propositions for peaceful cultural collaboration», Christos Karouzos, Director of the National Archaeological Museum, states in his interview of the 16th June 1945 to the philological periodical Eleftera Grammata. The same continues to say: «When the Germans entered the country, their archaeologists who formed a specific military «service for the protection of the art», first of all demanded from us to open the Museums right away, saying first that the war was now over, then that the antiquities will sustain damages if kept hidden, and then that in the time of war it was all the more necessary for people to seek refuge in art et c.»

Indeed, already in June 1941 Hans Ulrich von Schönebeck, archaeologist and Head of the Service for the Protection of the Art Monuments, had asked persistently for the re-opening of the National Museum. For this purpose, the occupation forces compiled a list of 103 statues with the request to be exhibited, among them the Poseidon of Artemision, the ephebe of Anticythera and the ephebe of Marathon, an order that was never implemented. According to Christos Karouzos: «The steady resistance of the archaeological service, saved the most important of our Museums from destruction and looting».

«The most substantial damage occurred in the old building in the days of the December Events nightmare» Semni Karouzou narrates. And continues: «Bombs fell on the roof, which was entirely of wood, but did not reach the ancient marbles, the buried deeply into the ground».

To uncover the buried antiquities was the main priority after the end of the war. Along with the anxiety about their fate: «What had happened under the thick layer of sand, which was the state of preservation of the buried sculptures…».

Moments from the recovery of the ancient statues describes for us in his own way George Seferis in the Days:

«Tuesday, 4th of June 1946

Noon in the Archaeological Museum. They now unbury – some in crates and some placed totally nude in the soil – the statues. In one of the old large halls, familiar to us since our school days with its rigid appearance that recalled somewhat the austere public library, the workers were digging with pickaxes and shovels. The floor, if one did not look at the ceiling, the windows and the walls with the golden inscriptions, could have been any other location of excavations. The statues sunken still in the earth, were visible from the waist up naked, planted in fate. …It was a resurrection dance of rising figures, a Day of Reckoning of bodies that filled you with mad joy».

Unique also was the emotion when in 1947 the first three halls of the museum were opened, in the new wing with its entrance on Tositsa street. As Semni Karouzou narrates: «It was the first presentation of antiquities after the war. At that time the 100 years since the founding of the French Archaeological School were also celebrated and it was the first gathering of archaeologists from all over the world. They had the opportunity among the other known and beloved artworks of the Museum to admire a new acquisition since the end of the occupation. A splendid Kouros with his name engraved on the statue base: Aristodikos».

However, «The building that was prepared with such care in the eyes of uncultivated people looked suitable for exploitation. If it was turned into a Hall of Justice, the value of properties in the area would increase, there were also given abundant promises that it would be easy to find in return a large plot of land. This threat was taking shape in the horizon, but also in some state offices, more and more clearly up until a few years ago» the Ephor of the Vase Collection points out adding the bitter remark «… If this had taken place, we would not have had a National Museum not even in the following fifty years».

The safekeeping of antiquities during the occupation and the ensuing care for the reconstitution of the National Archaeological Museum were posts of responsibility before which we stand today with respect, admiration and gratitude.

Dr Maria Lagogianni-Georgakarakos

Director of the National Archaeological Museum

Translation

Dr Katia Manteli

Archaeologist, Department of Prehistoric Antiquities

Acknowledgment:

Credit line: National Archaeological Museum, Athens/Photographic Archive.

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports /Archaeological Receipts Fund.