Exhibit of the month

Primordial love

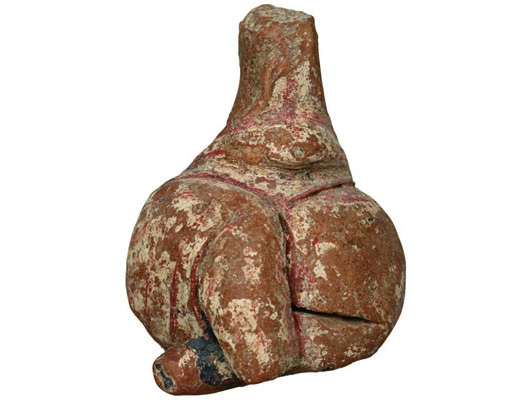

Clay figurine of seated female pregnant figure.

National Archaeological Museum

Sculpture Collection inv. no. Π 16488

Dimensions: Height 8 cm.

Provenance: Thessaly – Georgios Tsolosides Collection.

Date: Middle Neolithic (5800-5300 B.C.).

Using as starting point the collection of small-sized anthropomorphic figurines of the National Archaeological Museum, most of which come from the excavations of Christos Tsountas in the Neolithic agricultural settlements of Sesklo and Dimini in Thessaly, Greece, we will go back to unchartered aspects of prehistory and the realm of its symbolism in relation to gender, primordial love life and reproduction of the human species.

The bulk of figurines of the Early and Middle Neolithic period (6500-5300 B.C.) depict overweight female figures, emphasizing the areas of the body that relate to fertility (breasts, pubic triangle), while on the hips and buttocks there is excessive development of fat. Frequent is also the presence of pregnant women. On the contrary, male figures are less common.

Quite revealing is the fact that at least 30.000 years before the Neolithic period, in Europe of the Upper Palaeolithic era (45.000-10.000 B.C.), the communities of moving hunters and gatherers create the archetype of figurines portraying small female overweight figures. Their symbolism is not known to us nor the religious and ideological concepts of our Palaeolithic ancestors. What we see is the accentuation of female fertility, where fatness indicates health and abundance of food, the diachronic aim being genetic quality, healthy mothers and children.

Many interpretations have been proposed in the international bibliography not only for the figurines, but also for the manner of life, the primordial love and sexual reproduction. However, the most attractive amongst them remains that of Chris Knight, summarized by the short phrase ‘no meat, no sex’. In the Palaeolithic era, women, using the lunar calendar, synchronized their menstrual cycles, something that meant sexual abstinence. Thus, they forced men to go out hunting and bring back rich game and meat, when ‘the cycle of blood’ would have been completed and it would be possible to enjoy love-making under the light of the full moon.

It is not an exaggeration to view blood as the primary symbol of life and death in human societies. As a rule, the visible blood of women (menstruation, childbirth, placenta) is linked to life, while that of men to death (fatal injury). To the spectrum of red one should also add the colour of fire, so important for the survival of the human race (light, heating, food preparation, stone tool making, land clearing by controlled burning).

In the tradition of the Tungus and other people of Northeast Asia, some women kept even up to about 50 years ago in their tents a depiction of the ‘spirit of the hearth’, which they personified as ‘an intelligent, aged, but still strong and lively woman’.

In Siberia, contemporary reindeer hunters used lunar calendars. For instance, a mother would sew ten colourful strips to her garment in order to symbolize the ten lunar months of her pregnancy.

Moreover, according to the customs of the Igbo people, in southeast Nigeria, a pregnant woman carried always on her, placed in a purse, a small wooden doll painted red. When going down to the market, the other women were asking to see what was in her purse, then she would give them the doll, and they would rub it on their belly for the red colour to remain on their body and enhance their fertility.

The fact that many figurines of the Upper Palaeolithic are painted red may imply that there was an association of blood with fertility. Similar could have also been the significance of the red colour applied on the Neolithic figurines of Thessaly.

Dr. Katia Manteli

Bibliography

Gamble Clive, 1999. The Palaeolithic Societies of Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Knight Chris, 1991. Blood relations. Menstruation and the Origins of Culture. London and New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 327-373.

McDermott LeRoy, 1996. “Self-Representation in Upper Palaeolithic Female Figurines”, Current Anthropology, vol. 37, no. 2 (April), pp. 227-275.

Manteli Katia, 2018. «Figurines as holograms of beauty in the Neolithic culture of Greece. Rendering the human figure», in Maria Lagogianni-Georgakarakou (ed.) The Countless Aspects of Beauty in Ancient Art. Athens: Archaeological Receipts Fund, pp. 321-331.

Meyer Melissa, 2005. Thicker Than Water. The Origins of Blood as Symbol and Ritual. Oxford: Routledge, pp. 30-44.

Τσούντας Χρήστος, 1908. Αι Προϊστορικαί Ακροπόλεις Διμηνίου και Σέσκλου. Athens: Library of the Archaeological Society at Athens.

Χουρμουζιάδης Γιώργος Χ. 1994. Τα νεολιθικά ειδώλια. Thessaloniki: Vanias Publications.