Exhibit of the month

The face of farewell

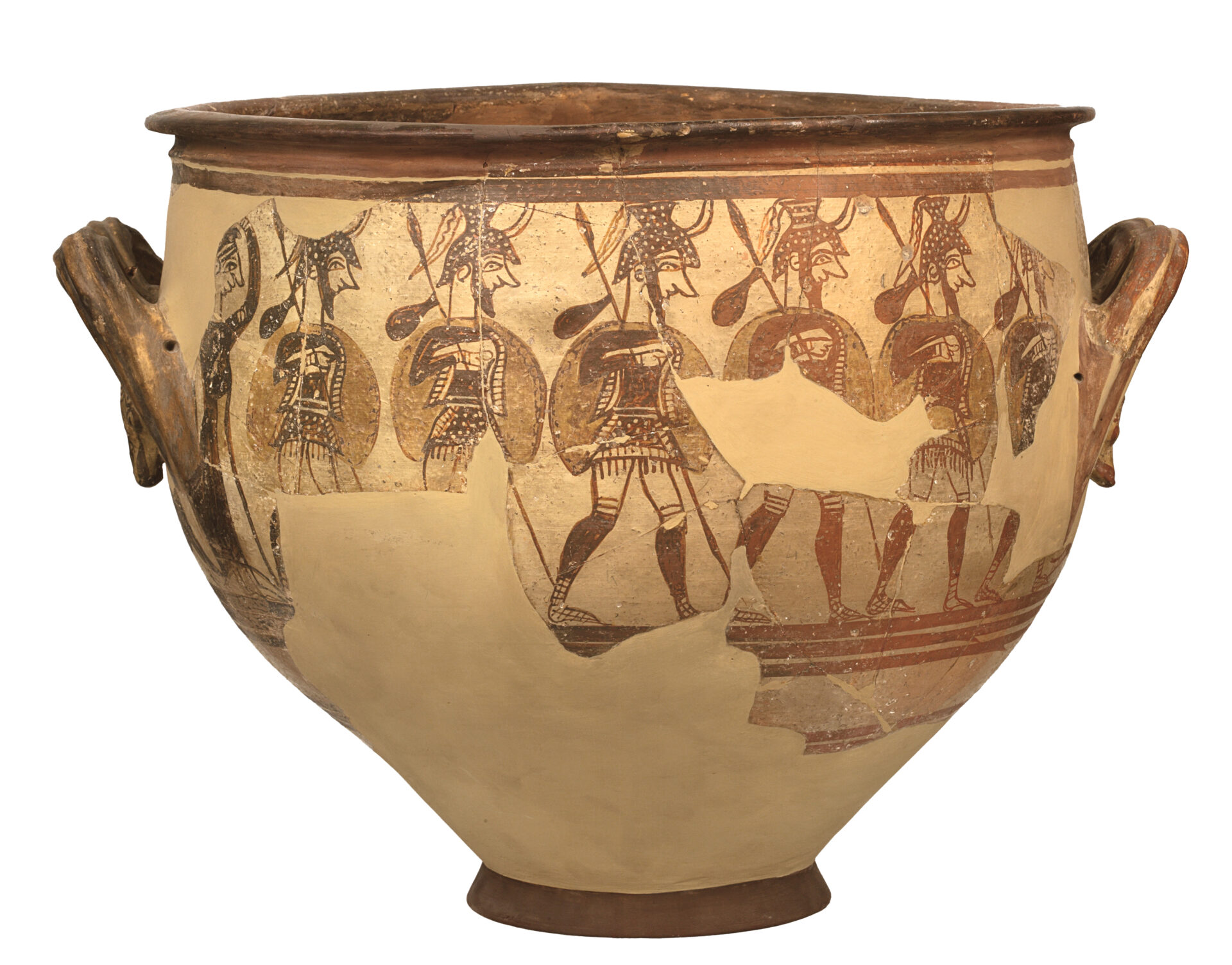

National Archaeological Museum, Exhibition of Prehistoric Antiquities inv. no. Π 1426

Provenance: House of the “Warrior Krater”, Mycenae citadel

Dimensions: height 42cm, rim diameter 50cm.

Date: 12th c. BC.

Display location: Exhibition of Mycenaean Antiquities, Room 4, showcase Μ19.

She stands at the edge of the scene on one side of the krater, half-hidden from the large double handle. When one views the vase frontally, she may be overlooked, as the hoplites setting off on a military expedition attract the viewer’s attention. This is how she would be standing in real life, at the edge of her village or the doorstep of her house, bidding farewell to the departing warriors. Her face denotes the anxiety of separation hoping to be temporary, the sadness of farewell, the agony for the fate of these young men; among them would perhaps be her children, her husband and her brothers[1].

The so-called Warrior Krater was collected in fragments by Heinrich Schliemann in 1876 within the Mycenae citadel, in a house which was named “House of the Warrior Krater” and was located immediately south of Grave Circle A. The vase was part of the banqueting set of the house or a grave marker[2] for a burial which took place in the post-palatial period after the abandonment of the building, given the krater’s good state of preservation and its large size.

The Warrior Krater constitutes a rare case where the two sides of a Mycenaean vase present two temporally consecutive scenes which narrate a warrior story. On one side the soldiers are seen marching in full battle gear, while on the other they have already reached the battlefield and are attacking by raising their spears in coordination. The woman in the first scene is wearing a long dress reaching her feet as well as a head cover and she is raising her hands: bidding farewell, praying, blessing. She may be on the margin of the picture, but her position is essentially significant. She defines the beginning of the narrative in time and space, the point from which the soldiers depart, but also where they long to return. This woman personifies family, home and country.

In Mycenaean art scenes of farewell[3] are rare and images depicting intense human emotions are mostly lacking[4]. The vase-painter of the krater[5], known as the “Stele Painter”, is a pioneer, not only in depicting narrative elements and expertly employing polychromy, but also in introducing a sentimental dimension in his work, surpassing the schematization of the art of his time.

[1] She may be a priestess blessing the departure or a simple woman, without official rank. She is certainly the Mother, the Wife, the Sister, the one that the ancient Greek writers later named Hecuba, Andromache, Antigone. It is no coincidence that the renowned Greek philologist I.Th. Kakridis considers “Hector’s and Andromache’s conversation” in book 6 the greatest scene in the Iliad. In this difficult moment of farewell, Andromache tells Hector «Ἕκτορ, ἀτὰρ σύ μοί ἐσσι πατὴρ καὶ πότνια μήτηρ ἠδὲ κασίγνητος, σὺ δέ μοι θαλερὸς παρακοίτης» (Il. 6, 429-430) – Nay, Hector, thou art to me father and queenly mother, thou art brother, and thou art my stalwart husband (transl. by Augustus Taber Murray). And the leading hero responds that he is not as sad for the misfortunes that will befall upon the Trojans, his mother Hecuba, his father Priam or his brothers, as he feels for her fate: «ὅσσον σεῦ, ὅτε κέν τις Ἀχαιῶν χαλκοχιτώνων δακρυόεσσαν ἄγηται, ἐλεύθερον ἦμαρ ἀπούρας» (Il. 6, 454-455) – as doth thy grief, when some brazen-coated Achaean shall lead thee away weeping and rob thee of thy day of freedom (transl. by Augustus Taber Murray). One is more important than family for the other.

[2] Using vases as grave markers was not unknown in the Mycenaean world, especially after the 12th c. BC, although it seems it never became common practice.

[3] Rare scenes of departure are included in the Naval Expedition fresco from Akrotiri, Thera, as well as on a gold ring [Exhibit of the month– January 2018 – https://www.namuseum.gr/monthly_artefact/o-apochorismos-ton-eroteymenon-2/] from Tiryns exhibited in the National Archaeological Museum (inv. no. Π6209, Exhibition of Mycenaean Antiquities, Room 4, showcase M28), where the departure of a ship is depicted and perhaps the separation or reunification of a couple. In historical times this subject will inspire masterpieces like the red-figured pelike by Aison depicting Theseus’ departure [Έκθεμα του μήνα – Φεβρουάριος 2016 – https://www.namuseum.gr/monthly_artefact/to-kateyodio/]

[4] With the exception of lament iconography and the expression of veneration in secular and religious scenes, instances where other human emotions are expressed with clarity and intensity are extremely rare. Among the exceptions is the ivory figurine [Exhibit of the month– June 2017 – https://www.namuseum.gr/monthly_artefact/scheseis-storgis/] from Mycenae, exhibited in the National Archaeological Museum (inv. no. Π7711, Exhibition of Mycenaean Antiquities, Room 4, showcase M18), where the three figures are connected by an affectionate relationship.

[5] The artist of the large krater is one of the last great vase-painters who worked in Mycenae. He was a “bilingual” artist, since he also decorated the well-known stone stele from Mycenae, using the technique of painting in fresco on plaster. The so called “Stele Painter” lived and created his works in the post-palatial period, at a time when the large palaces had received serious blows and arts like wall-painting were considered in decline. He may then have been the last Mycenaean wall-painter.

Dr Vassiliki Pliatsika

SUGGESTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Schliemann, H. Mykenae, Leipzig, 1878, σελ. 153 Nr. 213, σελ. 161 Nr 214.

Wace, A., Mycenae, An Archaeological History and Guide, Princeton 1949, pl. 82 a,b.

Vermeule E., Karageorghis V., Mycenaean Pictorial Vase Painting, Cambridge 1982, σελ. 130-132, XI.42.

Sakellarakis, J.The Pictorial Style in the National Archaeological Museum at Athens, Athens 1992, Νο. 32, σελ. 36-37.

Steele L., “Women in Mycenaean Pictorial Vase Painting” στοE. Rystedt and B. Wells (eds), Pictorial Pursuits. Figurative Painting on Mycenaean and Geometric Pottery, Acta Instituti Atheniensis Regni Sueciae 4o, LIII, Stockholm 1996, σελ. 147-155.

Crouwel, J., “Mycenaean Pictorial Pottery – Links with Wall-painting?” στο A. Vlachopoulos (ed.), Χρωστήρες. Paintbrushes. Wall-painting and Vase-painting of the second millennium BC in dialogue, Athens 2018, 98-99.