Exhibit of the month

What is god? What is not god? And what is in between?

Female figure head made of lime plaster, with plastic and painted features

Hellenic National Archaeological Museum, Collection of Prehistoric Antiquities inv. no. Π 4575

Provenance: Mycenae, Cult Centre

Dimensions: Height 0,168 m

Date: 12th c. BC

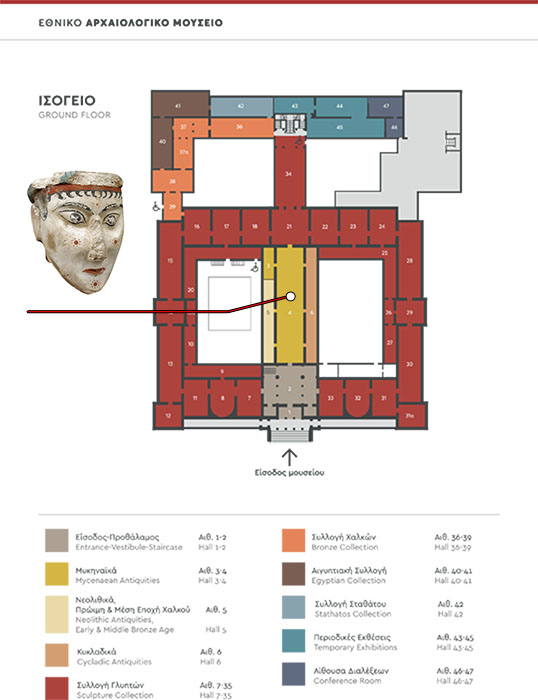

Display area: Room 4, Showcase 18

On July 3, 1896, Christos Tsountas in Mycenae notes in his excavation diary only a few words about one of the most important finds he ever brought to light: “In the citadel, in a corridor laying along the fortification wall, a woman’s head was found, made of lime plaster, colored, height 0.17 m”.

Despite the restrained tone of the initial entry, it is certain that at the moment of discovery, Tsountas held in awe the first Mycenaean sculpture of great size, since a little later he would write that “it is of the utmost importance for the history of Mycenaean and Greek sculpture in general; from this perspective, it can be considered an extremely valuable and completely unique find”[1].

It is a lime plaster head of a female figure, close to life-size, with plastic and painted features. The figure wears a flat blue cap with a red ribbon from which the ends of the hair hang on the forehead in a flame-like shape. The large almond-shaped eyes and arched eyebrows are rendered in black, the narrow lips are painted red, as are the ears[2]. Four red dot rosettes adorn the forehead, cheeks and chin[3]. Around the neck is a necklace with blue and red beads alternating, strung on a red thread. At the bottom there is a vertical hole for fixing with a peg to a trunk made of another material that has been lost, proving that the head was part of a large statue.

But who is this woman who looked at Tsountas from the depths of time?

“It seems difficult to me to accept that it represents a mortal woman,” writes the great archaeologist, “but it did not belong to a goddess either,” because in his opinion it would not have been rejected but would have been preserved “with greater reverence”[4].

So, what stands between humans and gods?

What is god? What is not god? And what is in between? (Euripides, Helen, 1137)

What is a god? What is not a god? And what is there in between them? (George Seferis, Helen, translated by Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard)

In the realm of mythological fantasy, in the borderland where the gods reside and the great heroes act, is where the monsters of mixed descent live. Tsountas was led to the conclusion that this female head represented a sphinx and even imagined her lion-like body seated, like the famous Egyptian one. And thus, this woman, with her serious enigmatic expression, has since been known as the Sphinx of Mycenae.

Since the late 19th century, our knowledge of Mycenaean religion has been dramatically enriched. We now know that large figures of deities were worshipped in small sanctuaries and temples at Mycenae, Tiryns, Asine, Midea, Phylakopi and elsewhere. Later excavations at Mycenae brought to light a second small head and a figurine, both made of lime plaster. Imaginary beings, such as sphinxes, accompany deities in iconography, but in Mycenaean Greece they never became objects of worship, much less statues.

The prevailing interpretation for the female head is that it represents a goddess, like the seated woman receiving offerings from demons on the large gold ring from Tiryns. Her name and attributes elude us, but her statue would certainly have played a leading role in the rituals of the Cult Center of Mycenae. Mysterious, solemn, enigmatic like a sphinx, but not a sphinx. Today, she awaits the visitor’s gaze in the large Mycenaean Hall of the Museum, while her own gaze is directed to the Mycenaean Lady, another exceptional female depiction, perhaps a representation of the same deity.

[1] Christos Tsountas, Excavation Diary 1896. Probably with the same thoughts that years later George Seferis expressed in poetic words: “[..] I look at the eyes: neither open nor closed/I speak to the mouth which keeps trying to speak/ I hold the cheeks which have broken through the skin. [..]” G. Seferis, 3 [I woke up…], Mythistorema (Athens 1935). [https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/51457/mythistorema]

[2] The emphasis on depicting the ears in red is typically found in religious depictions and is associated with ensuring the ability of the deity to hear the prayers of the faithful.

[3] Painted decoration on the cheeks and chin is observed also on the small lime plaster head and on the large wheel made female figures from Mycenae, which seem to have been used as images of the deities during the practice of worship. This decoration was obviously symbolic in nature, without it being known whether it was ever practiced in real life.

[4] Over time, it was proven that Christos Tsountas was right in his observation, since it has been ascertained in many cases that the Mycenaeans withdrew with care even the broken figures, figurines and ritual vessels.

Dr Vassiliki Pliatsika

Ενδεικτική βιβλιογραφία

F. Blakolmer, “A Pantheon without Attributes? Goddesses and Gods in Minoan and Mycenaean Iconography”, J. Mylonopoulos (ed.), Divine Images and Human Imaginations in Ancient Greece and Rome (2010) 21-61.

J.W. Earle, “Cosmetics and Cult Practices in the Bronze Age Aegean? A Case Study of Women with Red Ears”, Aegaeum 33 (2012), 771-777.

V. Pliatsika, “Simply Divine: The Jewellery, Dress and Body Adornment of the Mycenaean Clay Female Figures in Light of New Evidence from Mycenae”, Aegaeum 33 (2012), 609-626.

V. Pliatsika, “In search for the ideal Mycenaean lady: the aesthetic archetype of female beauty in the Mycenaean age”, Μ. Lagogianni-Georgakarakou (ed.), The Countless Aspects of Beauty in Ancient Art (2018) 355-369.

P.Rehak, “The ‘Sphinx’ Head from the Cult Centre at Mycenae”, A. Dakouri-Hild, S. Sherratt (ed.), Autochthon: Papers presented to O. T. P. K. Dickinson on the occasion of his retirement (2005) 271-275.

Χ. Τσούντας, [Μυκήναι], Πρακτικά Αρχαιολογικής Εταιρείας 1896, 31.

Χ. Τσούντας, «Κεφαλή εκ Μυκηνών», Αρχαιολογική Εφημερίς 1902, 1-10, πίν. 1-2.

Η. Palaiologou “A female painted plaster figure from Mycenae”, A. Vlachopoulos (ed.), Χρωστήρες. Paintbrushes. Wall-painting and Vase-painting of the second millennium BC in dialogue (2018), 95-125.