Exhibit of the month

The natural order and an apparent anomaly

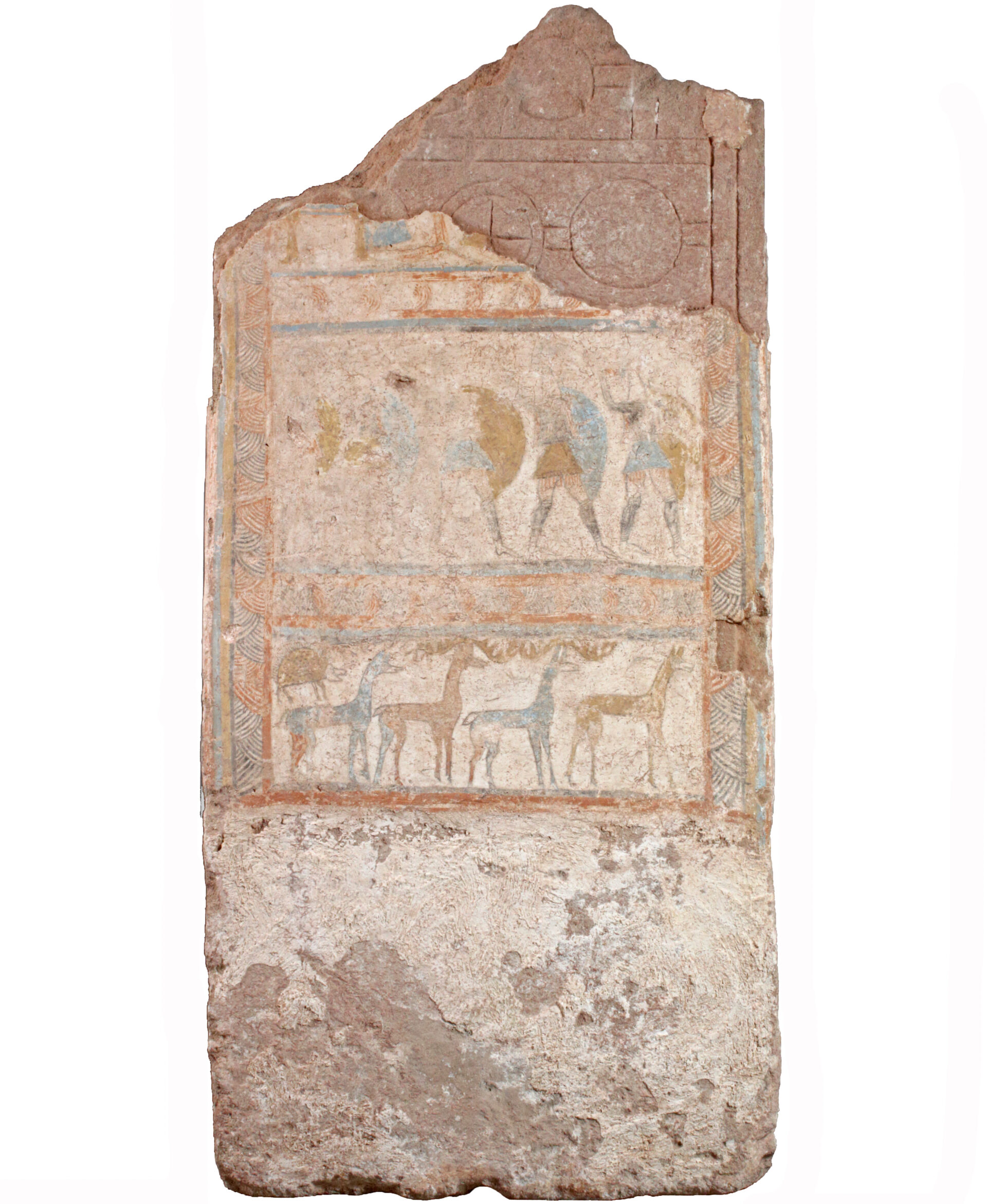

Stone stele covered in plaster with painted decoration in bands

Hellenic National Archaeological Museum

Collection of Prehistoric Antiquities inv. no. P 3256

Provenance: Mycenae, chamber tomb 70

Dimensions: Height 0.91 m, width 0.42 m, thickness 0.14 m.

Date: 12th c. BC

Display place: Room 4, Showcase 19

In 1893 the renowned archaeologist Christos Tsountas brought to light a find which remains unique to this day. During the excavation of chamber tomb 70 at Mycenae, a stone stele was discovered, decorated on the front with incised lines and circles. The stele was covered with lime plaster and had colorful fresco decoration with three superimposed friezes on the main face[1].

Although poorly preserved, the upper frieze probably depicts an encounter between a seated figure, certainly a person of authority (female or male, mortal or deity), and at least a second, possibly standing figure, facing the first[2].

In the middle frieze a procession of hoplites in full armor moves to the right with spears raised. The representation is similar to that which adorns one side of the Warrior Krater, a work by the same painter[3].

In the third frieze, stags move in procession to the right. A female leads and three horned males follow.

The iconographic program of the painted stele from Mycenae clearly summarizes the worldview of the Mycenaeans and their perception of the natural order. Reading the images from top to bottom and from left to right[4], just like today, the Mycenaean viewer realised that the gods (and/or secular rulers) of the first frieze are superior to the warriors of the middle one, who in turn are superior to the animals in the third zone.

Within the strictness of the order, however, lies an apparent anomaly: a hedgehog is depicted on the back of the last deer. If it does not function as one more representative of the animal kingdom represented in the third frieze, then it is possible that it is a subtle indication of the time when the burial took place and the tombstone was painted: hedgehogs hibernate and wake up in the spring and that’s why they were considered symbols of this season throughout time. They are also considered symbols of rebirth, so the pictorial choice befits the funerary iconography. But perhaps something even more interesting is taking place here, since the hedgehog does not walk on the ground, between the legs of the deer, but rides on board. This position of the animal, which does not comport with the nature of things at all, is a possible allusion to a mythological narrative, a Mycenaean tale that eludes us today.

[1] The stele had at least three phases of use. In the first phase it was sculpted and decorated with engraved motifs. In the second phase, in the 12th c. BC, it was covered with plaster, painted and used as a grave marker, partially buried in the ground. In the third phase the stele was used to close the opening of a niche that had been dug inside the chamber tomb 70, where it was found.

[2] Most scholars studying the stele agree that the upper frieze depicted a seated deity and at least one standing worshiping man, following the iconographic type of the “sacred conversation” known in Aegean iconography. Recently, the archaeologist Dr. Theodoros Iliopoulos interpreted the depicted piece of furniture not as a seat, but as a table of offerings or a bier, suggesting the depiction of a sacrifice or prothesis in the upper frieze.

[3] Another Mycenaean masterpiece attributed to the so-called “Stele Painter” is the famous Warrior Krater [Exhibit of the Month – May 2021 – https://www.namuseum.gr/en/monthly_artefact/the-face-of-farewell/]. This is a rare case of a “bilingual” artist who was acquainted with and created in at least two mediums, wall-painting and vase-painting. The painter worked in the 12th century BC, a time of change and crisis for the Mycenaean world marked by the gradual disintegration of the palatial system.

[4] Reading a series of images from left to right and from top to bottom coincides with the way the Mycenaean Linear B script was written and read.

Dr Vassiliki Pliatsika

Suggested Bibliography

Χ. Τσούντας, «Γραπτή Στήλη εκ Μυκηνών», Αρχαιολογική Εφημερίς 1896, σελ. 1-22.

E. Vermeule, V. Karageorghis, Mycenaean Pictorial Vase Painting, Cambridge Mass./London 1982, 132-134, 222, ΧI.43.

A. Σακελλαρίου, Οι Θαλαμωτοί τάφοι των Μυκηνών Ανασκαφής Χρ. Τσούντα (1887-1898), Paris 1985, 203-204, Λ 3256, έγχρωμος πίνακας.

Θ. Ηλιόπουλος, «Μια εικονογραφική παρατήρηση επί της ΥΕΙΙΙΓ «Γραπτής Στήλης» των Μυκηνών», Π. Αδάμ-Βελένη, Κ. Τζαναβάρη (επίμ.), Δινήεσσα, Τιμητικός τόμος για την Κατερίνα Ρωμιοπούλου, Θεσσαλονίκη 2012, σελ. 35-45.

V. Pliatsika, “The End Justifies the Means; Wall-painting Reflections in the Pictorial Pottery from Mycenae”, A. Vlachopoulos (ed.), Χρωστήρες. Paintbrushes. Wall-painting and Vase-painting of the second millennium BC in dialogue, Athens 2018, 535-545.

H.-G. Buchholz, “Echinos und Hystrix. Igel und Stachelschwein in Frühzeit und Antike”, Berliner Jahrbuch für Vor- und Frühgeschichte 5, 1965, 66-92. Buchholz H.-G., “Ostmediterrane Igel im Altertum”, Tier und Museum, Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft der Freunde und Förderer des museums Alexander Koenig – Bonn e. V., Band 4, Heft 2, März 1995, 33-49. A. Leonard, “Why a Hedgehog?”, L.E. Stager, J.A. Greene, M.D. Coogan (eds.), The Archaeology of Jordan and Beyond; Essays in Memory of James A. Sauer, 2000, 310-316.